- Home

- Natural Causes- The Nature Issue (retail) (epub)

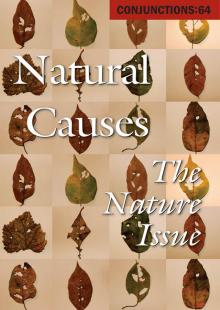

Conjunctions 64: Natural Causes

Conjunctions 64: Natural Causes Read online

EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

LOVE TO READ?

LOVE GREAT SALES?

GET FANTASTIC DEALS ON BESTSELLING EBOOKS

DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY!

Natural Causes

Conjunctions, Vol. 64

Edited by Bradford Morrow

CONJUNCTIONS

Bi-Annual Volumes of New Writing

Edited by

Bradford Morrow

Contributing Editors

John Ashbery

Martine Bellen

Mei-mei Berssenbrugge

Mary Caponegro

Brian Evenson

William H. Gass

Peter Gizzi

Robert Kelly

Ann Lauterbach

Norman Manea

Rick Moody

Howard Norman

Karen Russell

Joanna Scott

David Shields

Peter Straub

John Edgar Wideman

published by Bard College

Contents

Editor’s Note

Karen Hays, Frothy Elegance & Loose Concupiscence

Ann Lauterbach, After After Nature

Thomas Bernhard, Eight Poems (translated from German by James Reidel)

Russell Banks, Last Days Feeding Frenzy

Lucy Ives, Transformation Day

Martine Bellen, Two Poems

Benjamin Hale, Brother Who Comes Back Before the Next Very Big Winter

Evelyn Hampton, Fishmaker

Margaret Ross, Visiting Nanjing

Michael Ives, And the Bow Shall Be in the Cloud

Joyce Carol Oates, Big Burnt

Sequoia Nagamatsu, The Return to Monsterland

Christine Hume, Ventifacts

Lily Tuck, The Dead Swan

Greg Hrbek, The Confession of Philippe Delambre

Thalia Field, From Experimental Animals, A Reality Fiction

Diana George, Wara Wara

Wil Weitzel, Green Eyes of Harar

Meredith Stricker, Anemochore

Jessica Reed, Five Poems

Miranda Mellis, The Face Says Do Not Kill Me

Matthew Pitt, After the Jump

Noy Holland, Fire Feather Mendicant Broom

Sarah Mangold, From Her Wilderness Will Be Her Manners

Matthew Baker, Proof of the Monsters

China Miéville, Listen the Birds, A Trailer

Notes on Contributors

EDITOR’S NOTE

In smog-choked Nanjing with its vegetable vendors and on an island encircled by the pristine waters of Lake George and haunted by a doomed man’s memories, nature generates its own narratives in which humans play out their ordinary lives and, sometimes, extraordinary deaths. In the ancient city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia where hyenas come to feed in the sultry night and in the snowy Alaskan wilderness whose Russian River salmon are being greedily, hedonistically overfished, nature is observed, marveled at, even as it’s being exploited and threatened—together with its hapless human “custodians”—with extinction. Nature survives as best it can while we savor and pollute it, celebrate and misuse it. And as for its misuse, humans have long been an egregiously clever tribe of misusers. If, for instance, the Department of Defense has its way, as Christine Hume notes in these pages, weather itself could one day be weaponized using “weather-modification technologies [that] might give the United States a ‘weather edge’ over adversaries.”

Yet not all is apocalyptic. Nature has traditionally played a rich, central role in literature, sometimes becoming a character itself. Yes, a dead swan becomes a metaphor for a dying, violent marriage, but then springtime flora proposes rebirth, the promise of futurity. In these pages we encounter shrimp farms and spoonbills, maize husks and Austrian woods, tarantulas and eels, multitudinous winds that pollinate or desiccate—nature in all its myriad forms, right down to photons, neutrons, neutrinos, and, yes, even Godzilla, the Sasquatch, and other of nature’s fictive and folkloric monsters.

Natural Causes is less a dispatch from the Sierra Club—although concern for our environment and appreciation of its ravishing beauty and diversity are very much on the minds of these writers—than a reimagining of how nature writing can be written. Here are twenty-five engagements not only with our natural world but with the ways in which we contemplate it in art and essay.

—Bradford Morrow

April 2015

New York City

Frothy Elegance & Loose Concupiscence

Karen Hays

FROTHY ELEGANCE

To get to the fields this morning, the kids, most of them still too young to drive, ride in school buses, the route illumined by high beams, the drivers alert to deer along the shoulder, the sun canoodling and vexing the sleepy horizon as it stretches and procrastinates getting up, the smells of the Missouri countryside rising to the open bus windows—full-bodied, sour-sweet, piquant.

Each bus is a capsule of fireflies rocketing down the highway in the predawn dark. The jars are overfilled and their occupants drowsily blink on and off, on and off. Most slump and doze in upright fetal curls, their knees pressed into the unyielding green seat backs in front of them, their heads cocooned in soundscapes specially chosen to romanticize the unique brand of lust or angst or rage or heartbreak they seem to feel they suffer from, their faces lighting up with electronic glow whenever they stir to adjust the volume, or skip a song, or text a kid a few rows back or up, or whenever the bus dips into a pothole or veers onto the rumble strips, jarringly.

By the time they arrive, the light in the cornfields is crepuscular and it almost feels like morning out. As many girls as boys tumble off the buses, and both genders dress in the same work clothes. They wear long-sleeved shirts, heavy pants tucked into tube socks, and baseball caps or wide-brimmed hats. Because the dew is so heavy, they also don hull-like Hefty sacks. Bandannas enfold their necks like fallen crowns or forsaken brigand masks. On their feet are the boots or high-topped shoes they fully expect to pitch in the garbage when, a couple of weeks from now, their pockets will be loaded with cash, and their work mercifully done with.

The kids are brought in as a kind of cleanup crew, to get what the machinery has missed. The mechanical detasselers have already taken a pass through the fields, but about a third of the male flowers on the female-designated rows still linger. Those have to come off before pollen shed or else the females will pollinate themselves and the corn won’t crossbreed like it’s supposed to. To make a female corn plant out of a bull corn plant, all you have to do is snap off the tassel. Because variety is the key to producing robust offspring, bulls and females are grown from different seed stock. The better and heartier ears are hybrids.

When it comes to detasseling, there’s still no substitute for human hands. Over the medical tape, the kids, ages twelve and up, wear protective gloves. Some think they’re guarding against an allergic reaction, but the truth is, corn has glass in its leaves, little microscopic beads of opaline silica that keep animals from grazing its stalks down to spayed and neutered nubs. Because of the silica, corn leaves slice and rasp. Even when barely brushed against, a leaf of maize will impart a laceration as deep and fine as a paper cut. Walking a row unprotected will raise a whole terrain of welts that will itch and blister, weep and crust over, render wakefulness miserable and sleep next to impossible.

It’s a race to the end of each row, but whoever misses

a tassel loses. Here now a kid grabs hold of a stalk with one gloved hand and, with the other, snaps the tasseled end to the side, rights it, then yanks it straight off the top of the plant. He tosses the male flower on the ground where the wind will never gather the strength to lift and broadcast its pollen. Steps on it. The sound the stalk makes breaking is appetizing, like teeth in an apple or a rib of celery fracturing.

In maize leaves, the beads of glass are shaped like human molars. In other plants, the shapes are different.

•

The seed of the Missouri state motto was planted in 1899 when Congressman Willard Vandiver was pressured into giving a speech under somewhat awkward circumstances.

Vandiver was in Philadelphia on business when, “after a very busy day among the naval officers and the big guns and battle-ships and armor-plate shops,”1 he and several colleagues were unexpectedly invited to attend a formal dinner. Congressman Vandiver had nothing appropriate to wear and not much time to improvise. He was pleased to discover former governor Hull of Iowa in the same boat as he. As they were the only two invitees unprepared for a banquet, the two agreed, albeit reluctantly, to attend in casual clothes; each man would at least draw the thin comfort of knowing he wasn’t the only underdressed guest at the club. The two parted company, but while Vandiver relaxed for a few minutes, Hull scrambled to obtain dinner attire. As a result, Vandiver was the only man in two hundred not dressed in an evening suit for the banquet. Asked to stand and give a speech midway through, the humiliated Vandiver realized he “must crawl under the table and hide, or else defy the conventionalities and bull the market, so to speak.”2 Willard attempted to recover from his embarrassment by falling on the time-tested method of talking trash about his neighbor. He accused Hull of stealing his own dress suit and offered as proof the sloppiness with which the clothes hung from Hull’s frame. In his own words:

I made a rough-and-tumble speech, saying the meanest things I could think about the old Quaker town, telling them they were a hundred years behind the times, their city government was the worst in America, which was almost the truth, and various other things, in the worst style I could command; and then turning toward Governor Hull followed up with a roast something like this: “His talk about your hospitality is all bunk; he wants another feed. He tells you that the tailors, finding he was here without a dress-suit, made one for him in fifteen minutes. I have a different explanation; you heard him say he came over here without one and you see him now with one that doesn’t fit him. The explanation is that he stole mine, and that’s the reason why you see him with one on and me without any. This story from Iowa doesn’t go at all with me: I’m from Missouri, and you’ve got to show me.”3

According to Willard, the speech was a rousing success and induced ribald cheering all around. Soon it became a song. “He’s a good liar!” the crowd chorused in merriment.4

In Willard’s day, swindling and pomp were big entertainment. In the nineteenth century, medicine shows made tours of tiny towns in the Corn Belt, traveling by horse-drawn wagon and moving from north to south in a swath that coincided not with detasseling, but with the grain and cotton harvests, ideally staying in each backwater for two weeks at a stretch. Medicine shows featured everything from performing dogs to ventriloquists, fire-lickers, comedians in blackface, and pie-eating contests. All of this free revelry created a sense of indebtedness in the entertainment-starved audiences, making them extra suggestible when nostrum hawkers interrupted the frivolity to spew patter like this: “Is there some way you can delay, and perhaps for years, that final moment before your name is written down by a bony hand in the cold diary of death?”5 The answer, of course, provided by the snake-oil salesman, was “Yes” and quickly followed by: “Well, step right up then.”

What many don’t know is that “show me” and “Missouri” were paired long before Missouri adopted its state slogan. The two were connected in a way that was not meant to praise Missourians as keenly cynical and discerning but to pillory them. Missourians were considered by the residents of their neighboring states to be too dumb to grasp a situation or perform a task unless provided some kind of over-blown pantomime or explanation. It was more like, “Oh, Willard? No, no, no. You’ll have to show him if there’s to be any hope of him getting it.” Willard upended the insult and his vindicated statesmen ran with it. One journalist wrote this concerning the motto’s evolution: “Like the grain of dirt in the oyster shell […], the process of assimilation into the language of everyday life has transformed it from a phrase of opprobrium into a pearl of approbation.”6

The quote most often attributed to Vandiver is, “I come from a land of corn and cotton, cockleburs and democrats, and frothy elegance neither satisfies nor convinces me. I am from Missouri and you have got to show me.”

••

The same year that Vandiver is believed to have made his “frothy elegance” speech, Italian botanist Federico Delpino wrote this about the attention we pay to the sometimes-deceiving appearance of things: “What is morphology, if not the measure of our ignorance?”7

The first to study the actual functions of plants—then regarded as “curious accidents”—Delpino is considered by modern botanists to be the father of plant biology.8 Though history seems to have largely overlooked him, Delpino’s contributions to science were major. He was a fervent champion of Darwin and, as such, he worried that the theory of evolution would never be proven through traditional analyses of form or systematics. What was needed, Delpino argued, was a thorough understanding of how plants relate to one another and their environment. Delpino shared the results of his botanical observations with Darwin, maintaining an affectionate correspondence with him for years and signing his letters with valedictions such as “your most humble disciple,”9 “your most obedient disciple,”10 and “your true admirer and servant.”11

In the autumn of 1869, Delpino received an irresistible suggestion in the mail from his friend. In a letter he closed with “Believe me, dear Sir, with much respect, Yours very faithfully, Charles Darwin,” Darwin suggested his pen pal take up the study of grasses, corn in particular. He wrote, “Permit me to suggest to you to study next spring the fertilisation of the Graminaea […] Zea mays would be well worth studying.”12

Study he did, though communication was difficult between the two men. Some believe that Delpino’s contributions to botany were overlooked because he wrote only in Italian, a language typecast for romance, not science. Darwin had to have his wife translate Delpino’s letters before he could learn their contents. “It is a bitter grief to me that I cannot read Italian,”13 Darwin wrote to his Italian friend.

Perhaps it was this incompatibility of tongues—this deprivation of voices—that made Darwin wish he could lay eyes on Delpino. Perhaps Darwin wanted to assay the intolerable ignorance of languages by making a survey of Delpino’s appearance, by looking and also by revealing. “Pray oblige me by sending me your photograph,” wrote Charles after enduring a summer of poor health, “and I enclose one of my own in case you would like to possess it.”14

•••

Summer break lasts less than a quarter of the calendar year and each year it gets both shorter and hotter. The kids quit midday when the heat begins to feel apocalyptic. By midmorning the milk jugs they filled with water and put in the freezer before bed are melting into their least favorite but inarguably most quenching thing to drink in the field. Weeds and springtails and maimed daddy longlegs cling to the beads of condensation and to the jugs’ mud-smeared handles while the kids flirt and sing and talk trash to one another between the rows, looking insectile in their farmer-provided wraparound eyewear.

Rising temperatures make it a toss-up for the younger and more impetuous teens: Is it worse to swelter beneath all the cotton and the Hefty sack or to expose some skin to the glass and sun and insects, so that their sweat can do the job it was meant to, and the wind can relieve them?

In the fields, the

wind is everything.

When Delpino undertook the study of grasses, he discovered that, while some flowering plants rely on insects, birds, or bats for their pollination, others use wind. The first to classify “pollination syndromes,” Delpino labeled grasses like Zea mays “anemophilous,” or “wind-loving.” Simply put, corn loves the wind.

Though its method of fertilization is well understood, corn pollen remains a bit of a puzzle in terms of its appearance. What controls the size and geometry of a plant’s pollen are its method of dispersal and how ancestral or highly evolved it is. Evolution tends to lead to complexity of form, with more recent bodies exhibiting more elaborate designs. Though grasses like Zea mays are newcomers to the botanical scene, their pollen resembles that of the world’s oldest, most primitive plants. Corn pollen is modest in architecture. It lacks the baroque crimples and pores that render other species’ pollen so stunning under magnification. Absent are pointy stalagmites, Moorish tessellations, lacy fretwork, rolling folds, sticky pollenkit, lunar pocks, waving hairs, and so on. The pollen grains of Zea mays are just plain dry spheres, each possessing a single mouthlike aperture for its sperm to escape from. Where other pollen varieties resemble modern sculpture in their intricacy and elegance, a grain of maize pollen resembles nothing so much as an overstuffed beanbag chair.

One explanation for maize pollen’s surprising simplicity of form is that possessing a single feature—the mouthlike pore—weights the grain so that it’s more likely to find itself aperture down when it lands, improving its odds of making meaningful contact with a strand of silk, or corn stigma, should it be so lucky as to alight on one. Helping to weight the grain is the fish-lipped, or “crassimarginate,” nature of its pore. (A note on etymology here: Before it meant “crude,” “earthy,” and “unrefined,” “crass” was used to designate objects that were literally thick or fat. The process of assimilation has turned “crass” into an adjective of opprobrium.) The pore is also termed “opercular,” as in the little circular door that snails close when they don’t care to be messed with.

Conjunctions 64: Natural Causes

Conjunctions 64: Natural Causes